Our short drive from St German’s Church (see part one of our welsh organ pilgrimage) took us to Llandaff Cathedral.

Third stop on Organ trip – Llandaff Cathedral

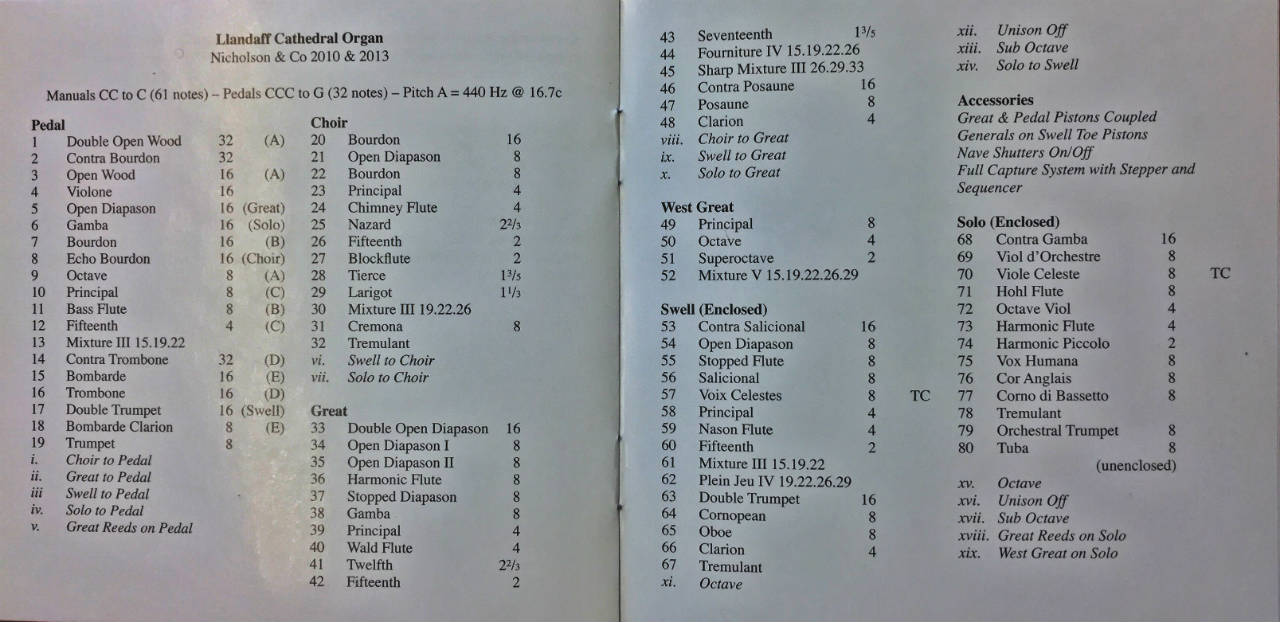

Llandaff Cathedral now has a 4 manual organ built by Nicholson of Worcester. Substantially completed in 2010 the final solo organ stops were added in 2013. See the NPOR register entry and the information on the Nicholson website. One of our instruments was temporarily installed to provide the music during the rebuild between 2008 and 2010.

A little after 7.30pm we were met by Stephen Moore the recently appointed Director of Music and ushered in through the range of buildings to the west of the cathedral that lead to the ‘Welch Regiment Chapel’ added in the 1950’s and finally into the Cathedral from the north.

There is something quite magical about being one of just two or three people alone at night in one of our great cathedral buildings. There is an inevitable sense of privilege that one is trusted but also the scale of the building seems all the more significant when otherwise so empty, its as if it is sending a message of one’s own significance – or lack of – in the universe.

Llandaff is a building I have known since I was 5 years old when I attended the Cathedral School and so often attended services there when Dr Robert Joyce was the organist and choirmaster.

The history of organs at Llandaff Cathedral

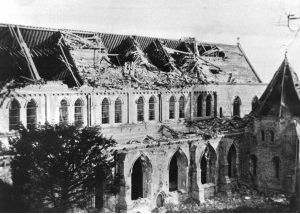

The first substantial organ at Llandaff was built in 1861 by Gray & Davidson. This instrument moved to St Mary’s Usk in 1898 (where it remains) and was replaced by an instrument designed by Hope-Jones which remained in use until destroyed by war damage in 1941.

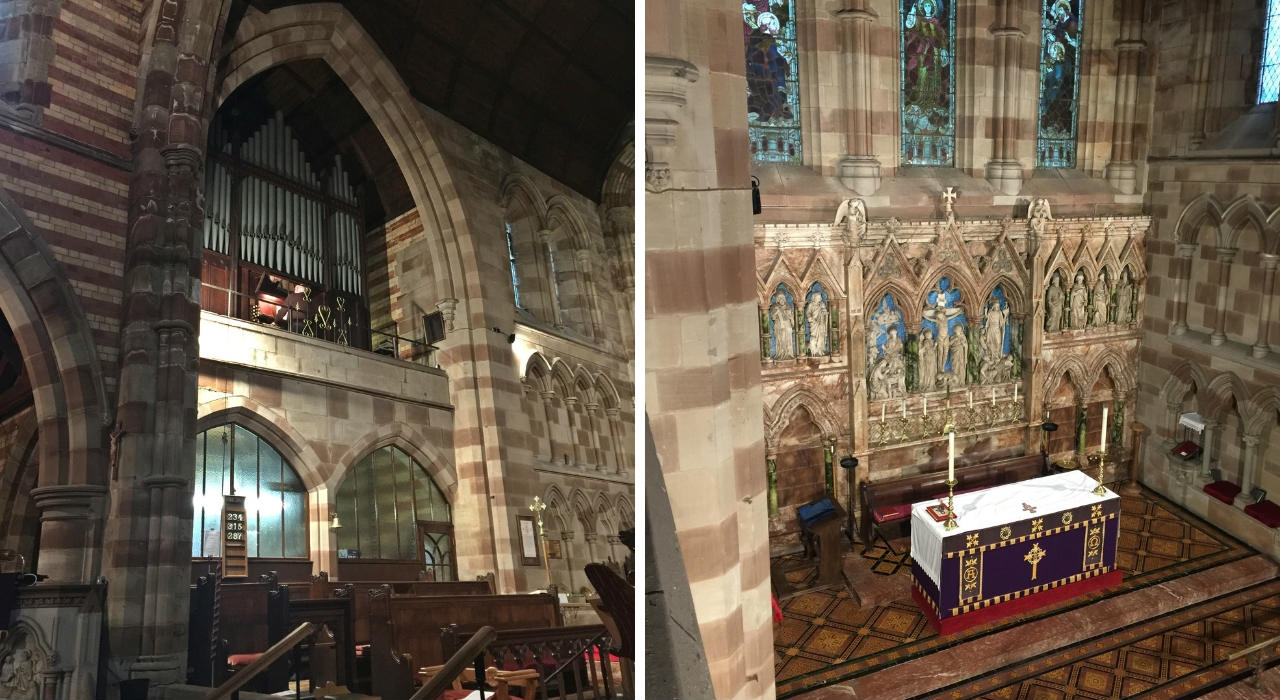

The building was fully restored by 1958 when a new organ by Hill Norman & Beard was built incorporating what pipe work could be salvaged from its bomb-damaged Hope-Jones predecessor. The positive division of this instrument was built inside the concrete cylinder of the architect Pace’s ‘modern’ interpretation of a choir screen that also carries the Epstein statue of ‘Christ in Majesty’.

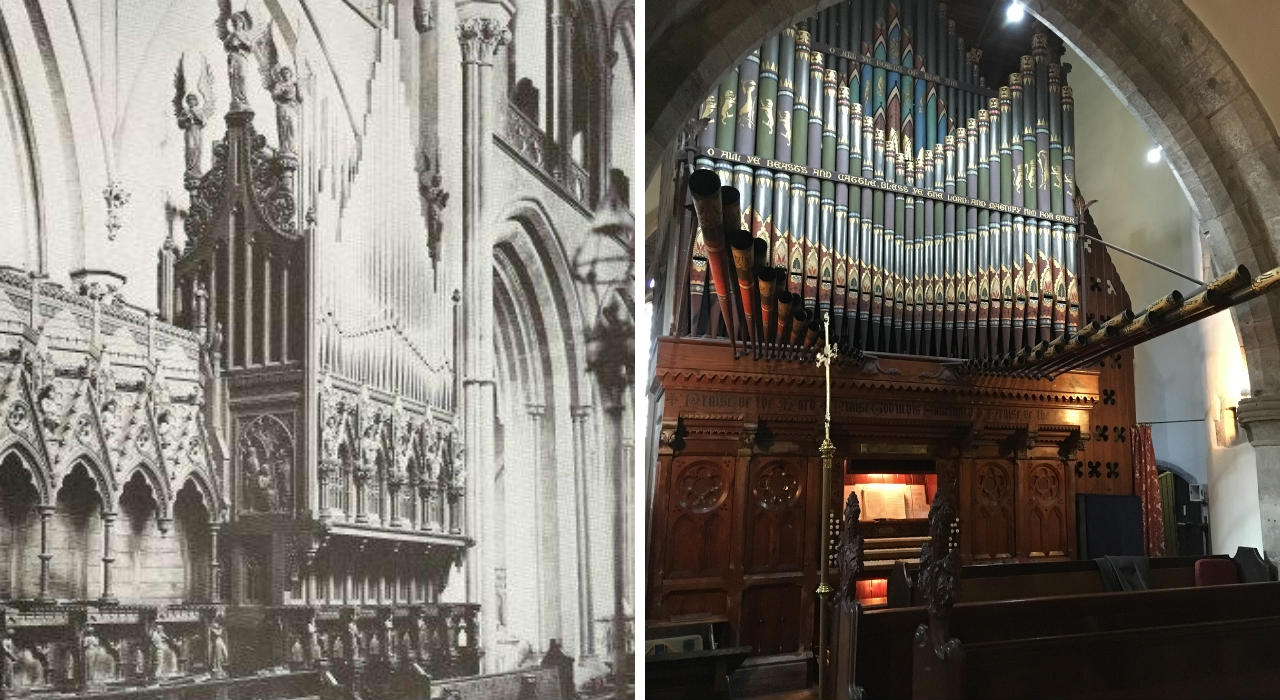

Apparently, this was one of the most dangerous tuning jobs anywhere in the country as access to the pipe chamber is perhaps 30 ft above the nave floor through a trap door on the underside of the structure. I had always thought that the ‘angels’ that adorn the side elevations of the huge ‘concrete tube’ were also part of Epstein’s work but these are actually wooden carvings that were part of the early choir stalls and recycled for the purpose. You can just about make them out in the rather grainy picture of the Cathedral’s Hope-Jones Organ.

The Pipe Organ at Llandaff Cathedral shocks us

We made our way to the lovely and spacious new loft, a bay east of its former position and were given a short-guided tour of console and facilities and then left alone for an hour to explore the vast array of colours at one’s disposal.

To my mind an organ is at its best when it whispers, especially when in a huge space. There is something ethereal when very quiet strings are shimmering in the background against a quite solo line. The choir organ here is unenclosed so that really quiet sound is only available from the swell with box closed and perhaps with hindsight an enclosed choir department would have given more options, but that apart this is a very fine example of British organ building.

At the other end of the dynamic range there is an abundance of power which requires careful use. The main great chorus is duplicated in a west facing case on the north aisle and this can be added if required to substantially boost the volume for a full cathedral. The console sits beside the swell and choir divisions with great pedal and solo opposite on the north so the musician does get to hear very well all that is going on.

At one point I added a piston that brought on the 32 ft pedal reed and actually stopped playing such was its dominance at the console but I am assured that in the nave the balance is far more comfortable. At the console though for the first time it was quite a shock!

At such a large instrument an hour is hardly enough to scratch the surface, so the visit came to an end all to soon. We lingered perhaps for a further 15 minutes chatting to Stephen and just enjoying the elegance and tranquillity of the space. Before the roof was destroyed in 1941 its structure was a much more conventional, heavily beamed and pitched so creating a space of far greater height. The acoustic has no doubt changed by the installation of a flat roof. I wonder if it has gained or lost by this change?

You can hear this Nicholson instrument played by their organist David Thomas below. A recording I made on my iPhone at the conclusion of a service last year while I was visiting Llandaff Cathedral.

Emerging into a light rain-soaked evening I made my way just a few 100 yards to the Malsters pub for my evening bed and very much looking forward to the full day that lay ahead.

St Peter’s Church our fourth stop

An early start was required next morning as we had to get to St Peter’s in Pentre by 9.00am to meet the vicar Haydn England- Simon. St Peter’s is another church in the Anglo Catholic tradition sometimes I gather known as the Cathedral of the Rhondda.

It was built in Early English style in 1888-89 to designs of F.R. Kempson and J.B. Fowler, Llandaff diocesan architects, commissioned by church benefactor Griffith Llewellyn of Baglan. The church is constructed of coursed pink and buff Pennant sandstone.

It is a lofty impressive building with a bell-tower housing the heaviest ring of eight bells in Wales. The interior throughout is dominated by the contrasting bands of pink and buff-coloured brick which my guide humorously refers to as the streaky bacon school of decoration. The fittings include a magnificent wall-to-wall reredos of pink-veined marble, Penarth Alabaster, with white marble figures under canopies and some fine stained glass by W.F.Dixon.

The Willis Organ at St Peter’s Church

The instrument drawing us here was an original Willis organ dating from 1890 so like everything else in this church the organ too was of the highest quality available at the time demonstrating how the wealth generated from welsh coal were lavished by the coal owners on creating legacy (or vanity?) landmarks. This is small instrument of just 19 speaking stops but as you will hear from our recording it can build up to a very fine and rich sound in this church even though it sits a little tucked away in a north gallery high above the choir.

Its condition now is a little battered with a key veneer and some stop discs missing. It would appear to be pretty much unchanged save for a Corno di Basetto once on the Great is now on the Swell leaving the Great rank space empty. One perhaps must guess this ‘transplant’ ejected another small reed rank but what it was and why it was changed is a mystery.

On the day of our visit some of the pipes clearly needed tuning but for the most part it was acoustically still in very good shape. Judge for yourself by listening below.

… and on to the next Welsh Organ

We said our farewells at about 10.30am to head for the nearby church of St George’s Cwm Parc where the installed Viscount organ was to have some external speakers added. After an hour or so there we headed north into the Brecon Beacons but to learn about what lay ahead for the rest of the day you will have to wait for the third and final part of this write up.

*I am grateful for the historic information on past instruments in David Thomas’s short booklet history of the Organs of Llandaff Cathedral.

<< Read Part One of the Welsh Church Organ Pilgrimage

Read Part Three of the Welsh Church Organ Pilgrimage >>

I have had a passion for church organs since the tender age of 12. I own and run Viscount Organs with a close attention to the detail that musicians appreciate; and a clear understanding of the benefits of digital technology and keeping to the traditional and emotional elements of organ playing.