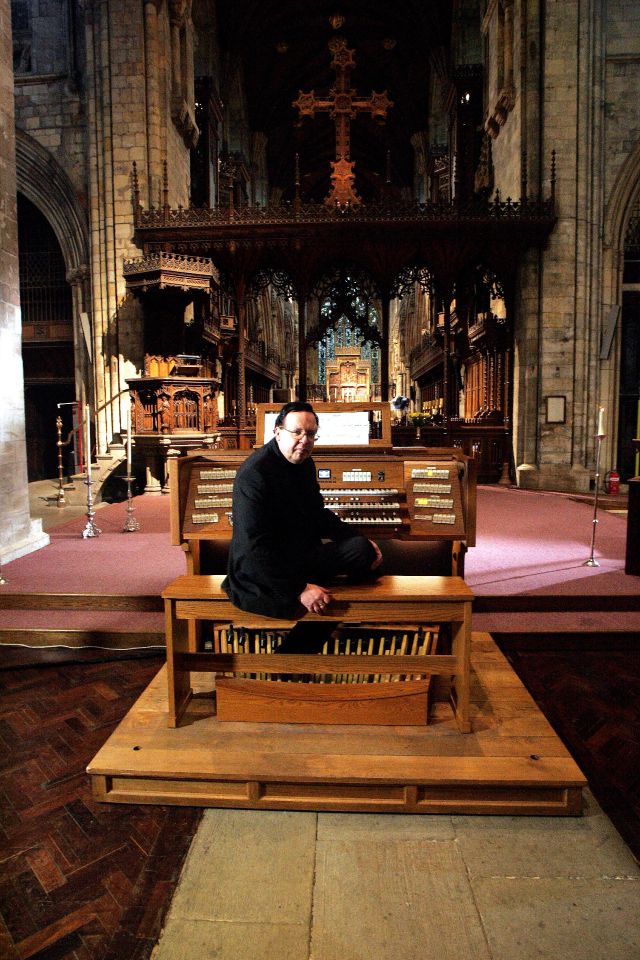

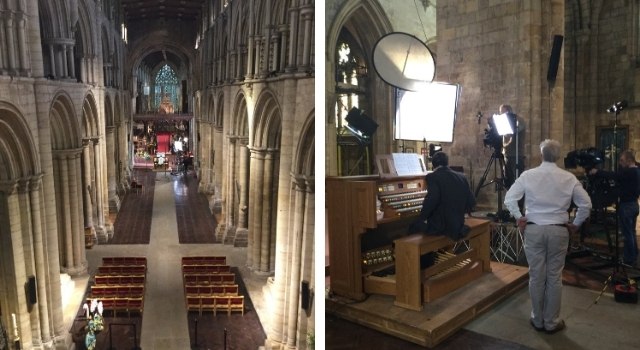

In 2015 we recorded a series of performances by John Scott Whiteley, for a DVD entitled “Paths that lead away from Bach”. The sessions took place in the dramatic setting of Selby Abbey, where a Viscount Regent 356 organ was temporarily installed while the Abbey’s famous Hill organ was being restored.

John Scott Whiteley English Organist and Composer

John Scott Whiteley is Organist Emeritus of York Minster, having worked at that great institution for 35 years until his retirement from it in 2010.

In 2014 he was elected to the Worshipful Company of Musicians, in recognition of his promotion of the organ and its music. He is a well-known and successful recitalist, and has made numerous recordings. A particular specialism is the music of J.S. Bach, and John recently worked on a comprehensive series of broadcasts for the BBC entitled “21st Century Bach”, which aimed to cover the composer’s entire works for the organ.

“Paths that lead away from Bach” by Whiteley

“Paths that lead away from Bach” is a particularly interesting set of recordings, not least because of its exploration of the various tunings and temperaments that were being used around Bach’s time.

This may seem involved and unusual to us today, because we have become used to a largely standardised approach to tuning known as equal temperament, which enables pieces to be played in any key. Equal temperament is a compromise that distributes deviations from natural tuning across the chromatic scale by making all the semitones the same “size” (in terms of their frequency ratio). The result is not perfectly “in tune” in any key, but equally “out of tune” in every key, and it sort of works for the majority of applications.

In Bach’s day, however, all sorts of alternatives were available, which distributed the tuning compromises differently across the notes of the scale. They all had their adherents, and strenuous arguments were had over which one was the “best”. The results had varying degrees of success, and would typically sound pleasing when playing close to the base key (the one in which the organ was most in tune), but increasingly painful when playing in the more remote keys. Certain intervals could “howl” unpleasantly, while others would sound more acoustically in tune than they are in equal temperament.

As John Scott Whiteley points out in his introduction to the DVD, the so-called Werckmeister III temperament became a popular tuning for organs in Germany in the 18th century, and this is used for a number of the pieces included in our series of performances.

There is, however, one piece in which JSW experiments with Kellner 75, an attempt at reconstructing the “well tempered” tuning that Bach arrived at during his own experiments. Another is Silbermann, a tuning adapted by the famous German organ builder, which struggles in keys such as A flat or F minor. You’ll hear examples of all three tunings on pieces in this series.

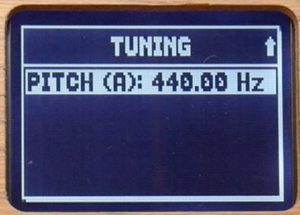

The other thing the eagle-eared will notice is that the organ in these performances is not always sounding at modern pitch.

The pitch of concert A = 440 Hz is a relatively recent thing, determined in the twentieth century, in an attempt to unify pitch standards across the world (only partially successful!). (One only has to think “Peterborough Cathedral” to be reminded of the problems that can arise from organs tuned to different pitch standards.)

The pitch of concert A = 440 Hz is a relatively recent thing, determined in the twentieth century, in an attempt to unify pitch standards across the world (only partially successful!). (One only has to think “Peterborough Cathedral” to be reminded of the problems that can arise from organs tuned to different pitch standards.)

In Bach’s day things were nothing like as predictable as they are now. JSW points out that a number of organs were tuned to “Chorton” (choir pitch), which was likely a semitone higher than today’s concert pitch, with A around 466 Hz. A number of these pieces are therefore played at that pitch.

One of the features of Viscount’s digital church organ systems is the relative ease with which temperament and tuning can be changed. All of the above temperaments (and others) were able to be experimented with on the Regent 356 used in these recordings, and the organ could be fine-tuned to any pitch standard, as shown in the pictures. This makes it possible for us to hear the interesting effects of unusual tunings without having to travel miles to play historic instruments.

The Regent 356 organ you hear is a versatile three manual instrument with 56 tab stops, employing the Physis method of organ tone synthesis that is based on physical modelling of the way real organ pipes behave.

Videos from “Paths that lead away from Bach”

“Paths that lead away from Bach” is an interesting exploration of associations between Bach’s music and that of his disciples, associates, rivals and pupils of the time. We start with two pieces by JSB himself, moving through pieces that may have been by his sons, to those by the less well-known Kauffmann, Krebs, Schneider, Kellner, Kittel and Müthel.

1. J.S. Bach: Fugue in G (“The Jig”) (BWV 577)

J.S. Bach’s “Fugue à la gigue” is often so-called because it’s in 12/8 time, and bounces along like a jig dance. It’s a popular piece, and quite a challenge for the organist, who ends up dancing something of a jig on the pedals.

As with “Vater unser”, which comes next in our series, Peter Williams suggests that some doubts have been cast on JSB being the composer, although it’s not clear who did write it. No firm conclusion seems to have been reached.

You hear it here played in Werckmeister III temperament at Chorton pitch.

2. J.S. Bach: Vater unser in Himmelreich (BWV 762)

This chorale prelude based on the melody “Our father which art in heaven” exists in a copy by Krebs, and Peter Williams suggests that it may indeed be by J.T. Krebs, or perhaps one of Bach’s other pupils.

It is played here in the “Kellner” temperament, an attempt to reconstruct Bach’s approach to “well-tempered” tuning, and at the Chorton pitch mentioned above. You’ll hear some interesting differences from what we know as equal temperament.

The melody is brought out on a Cornet mixture, which is a useful solo registration for such chorale preludes, either with or without tremulant for added expressiveness. It is a combination with a character that cuts through the accompaniment, dominated by the odd harmonic mutations, 12th (nazard) and 17th (tierce), usually of flute tone, on top of an 8-4-(2) flute foundation.

3. C.P.E. Bach: Fugue in B minor

The performer explains that this fugue was arranged by the organist K.H.L. Pölitz, from a Passion setting by C.P.E. Bach. Scott Whiteley suggests that it works in a temperament such as Werckmeister III (as done here), but would have probably been impossible on the Hamburg organs with which CPE was familiar, whose temperaments were relatively crude.

These organs would have been tuned to an even higher pitch known as Höhe Chorton (high choir pitch), and the eagle-eyed/eyed will notice that this performance sounds around a tone higher than the notes played.

4. W.F. Bach: Trio – “Wir Christenleut”

In his programme notes, Scott Whiteley explains that this trio on the chorale “Wir Christenleut” (We Christian Folk) by Bach’s son Wilhelm Friedemann is still alleged to be by his father JSB in some editions. This is possibly because Friedemann became destitute later in his life and may have used his father’s name on manuscripts to increase their value.

JSW plays the piece here in Silbermann temperament at concert pitch.

5. W.F. and/or J.S. Bach: Prelude and Fugue in F minor (BWV 534)

At least the fugue of this was probably written by W.F. Bach, according to a Dutch scholar, Peter Dirksen, says Whiteley. Organs tuned to the Silbermann temperament were reportedly “excruciating” to hear in remote flat keys such as F minor.

In this performance Scott Whiteley transposes it up to G minor, where it becomes more possible, still using the Silbermann temperament.

I have had a passion for church organs since the tender age of 12. I own and run Viscount Organs with a close attention to the detail that musicians appreciate; and a clear understanding of the benefits of digital technology and keeping to the traditional and emotional elements of organ playing.