This post is part of a series where I share some of my world travels, which my love for organs has taken me. I help friends, associates and fellow organ lovers with projects that mean I get to see new and old organs in gorgeous settings and really experiment with this instrument.

There are many reasons to visit the City of Lights, as we did in early September. We caught a glorious week of late summer sun – perfect for soaking up life à la Seine – but my reason for a trip, as ever, shone the spotlight on a wonderful church and great organ.

A church a little less ordinary

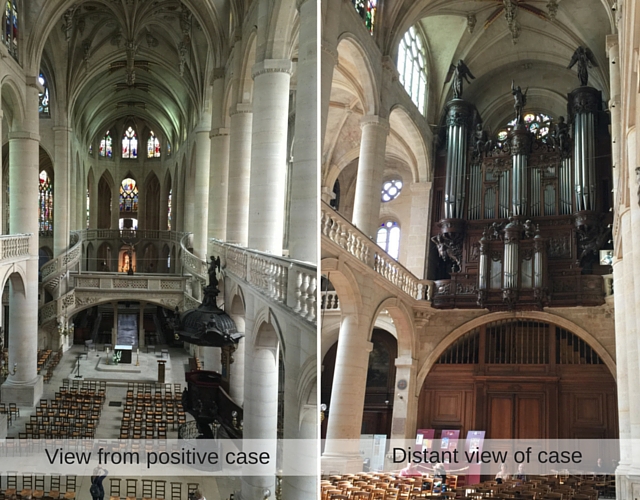

My rendezvous was at Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, a magnificent Gothic church, which mostly dates from the mid 1500’s. It’s dominated by a central stone rood loft with extraordinary spiral stairs (pictured right), which turn in opposing directions on the north and south sides – the handiwork of Father Biard in 1545. The church is a stone’s throw from Notre Dame on the south bank and almost adjacent to the Panthéon. It’s also next door to an English pub, The Bombardier, a very unusual feature. As we would find later when recording, this bonus was a bit of a mixed blessing. The pub serves excellent draft beer and if Trip Advisor is anything to go by, it has credentials as the best English pub in Paris. Santé!

My rendezvous was at Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, a magnificent Gothic church, which mostly dates from the mid 1500’s. It’s dominated by a central stone rood loft with extraordinary spiral stairs (pictured right), which turn in opposing directions on the north and south sides – the handiwork of Father Biard in 1545. The church is a stone’s throw from Notre Dame on the south bank and almost adjacent to the Panthéon. It’s also next door to an English pub, The Bombardier, a very unusual feature. As we would find later when recording, this bonus was a bit of a mixed blessing. The pub serves excellent draft beer and if Trip Advisor is anything to go by, it has credentials as the best English pub in Paris. Santé!

On the bill

Saint-Étienne-du-Mont was Durufle’s church and the programme chosen paid homage to this legacy. My employer for the trip was doing one of his usual demanding programmes, including the complete ‘Durufle Suite’ along with the first ever recording of a work by David Briggs, ‘Le Tombeau du Durufle’.

The piece de résistance

The organ at St Etienne is considered to have the best case of any in Paris. Dating from 1633, it was built by Jean Buron. The organ was completed in 1636 by Pierre le Pescheur. A masterpiece, it’s perhaps the most beautiful organ case in the French capital (pictured above). It’s certainly the oldest case that’s been completely preserved. Back in 1760, the organ was badly damaged in a fire. Francois-Henri Clicquot rebuilt it in 1777, completing works carried out by Nicolas Somer, who died in 1771. Aristide Cavaillé-Coll then revised the organ again in 1863.

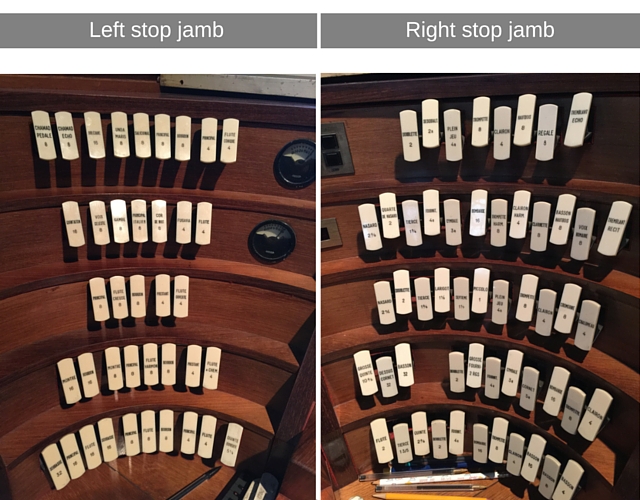

Today, the organ is very much a personal creation of Durufle, with revision carried out by Beuchet-Debierre in 1956, and a complete re-voicing of the instrument in 1975 by Gonzalez, who also electrified the action and installed the new console in the north transept gallery. There are 39 original stops dating from before the French Revolution, but they’re severely altered – only 7 are still in their original place and 6 are courtesy of Cavaillé-Coll. A new solo division sits remotely to the north of the case by some 10 metres and the entire pedal division sits unusually below the main case speaking through the arched opening. You can just see some of the pipes laying horizontally through the grille.

There are an unusually large number of mixture stops for a French organ and the 32-foot pedal reed – a basson is of tiny scale, is not heard at all when the organ is at full tilt The chamades are huge, as you’d expect, but also unusual, at least in my experience in France, are sub and super octave couplers for all 4 manuals and a general crescendo pedal. The new console also provides a full capture action with 15 generals and a stepper, which makes the page-turner/registrant job so much easier.

Setting up shop

We spent the Tuesday evening preparing registrations and took a well-earned rest towards midnight in The Bombardier.

On Wednesday, the organ wasn’t touched, giving the tuners a full day to bring the instrument into closer tune. This led to a difference of opinion between player and assistant. I know that part of the signature of the large French instruments is the looseness of tuning- but is that intentional or a consequence of the difficulty of keeping so many pipes at their correct pitch? Certainly, the evening temperature in the loft was getting uncomfortable, so regardless of tuning integrity at the start of the day, by evening the flues will have drifted away from the reeds. Whatever, I felt it was too far adrift, but the player was content.

However ,it meant time off for us, so we did a spot of sightseeing and managed to clock a couple of other great Paris organs – the Cliquot in the Cathedral des Invalides and the Cavaille-Coll at St Xaviers (all pictured below), before ticking off the city’s most iconic monument, the Eiffel Tower.

By Thurdsay and after a full days’ tuning, the instrument was far more enjoyable to my ear. My only remaining concern was the speed of speech of the recit Oboe, which had to jump to it, for the staccato melody lines in the ‘Vierne Scherzo’ from the 6th Symphony –an achievement it stubbornly resisted on some of the lower pitch notes.

And, action…

The first recording session on the Thursday evening went brilliantly and the entire programme, save for the Briggs, was completed. We had the usual registrant errors adding to the tension. A perfect take of the Durufle Toccata ruined by hitting a piston that brought the organ to complete silence. This did add some aggression into the next take, the pedal theme entered take 2 with a cutting power I hadn’t heard before and really underpinned the most dramatic interpretation of this Toccata you’re ever likely to hear. So if you like this most virile interpretation it may in part have been due to my blunder – and if you don’t it clearly was due to my blunder!

The ‘Vierne Scherzo’ has to be one of the most technically demanding pieces ever written. The manual changes are hard enough, but the rhythmic patterns working against each other in the hands and the jumping melody that represents the gargoyles hurling themselves about on Notre Dame’s roof is sensationally hard. You just can’t play it unless you’re amazingly agile with a quick mind to match.

The Briggs composition is in 11 contrasting sections, reflecting the life of Christ and is based on the Veni Creator. Some years ago, working for the same musician at St Ouen Rouen in September meant the recording coincided with University fresher week and the same was true this time at St Etienne, being right in the heart of the Sorbonne campus area. When on Friday we arrived at the church, we were greeted by a host of medical students gathering on the church steps, no doubt lured by the fine English ale served just a few meters away. They were warming up for what I imagine proved to be a night of considerable revelry. The prospect for quiet recording time evaporated before our very eyes.

Happily, there is much in the Briggs that requires full organ and the opening movement ‘Veni Creator’ starts with FFF! By the time this was finished the students had thankfully moved on never to be seen or heard again. Organ 1 – Students nil. The workload for me in this piece was happily confined to page turning, with each section maintaining an almost fixed registration from beginning to end.

This complete work played strictly to the marked metronome speed and allowing a little for the acoustic of St Etienne – lasts a full 22 minutes and was completed in 2 hours. The recording team was the same who worked with us at St Sernin last year – recording engineer Mike Hatch, assisted by George Collins and produced by Tim Oldham.

The other works on the disc are the Tournemire improvisation on the Te Deum, transcribed by Durufle and the Vierne Phantoms and the finale from Vierne Symphony no 5.

The disc will be released in 2016 on the Signum label. Look out for it – great music on a great organ!

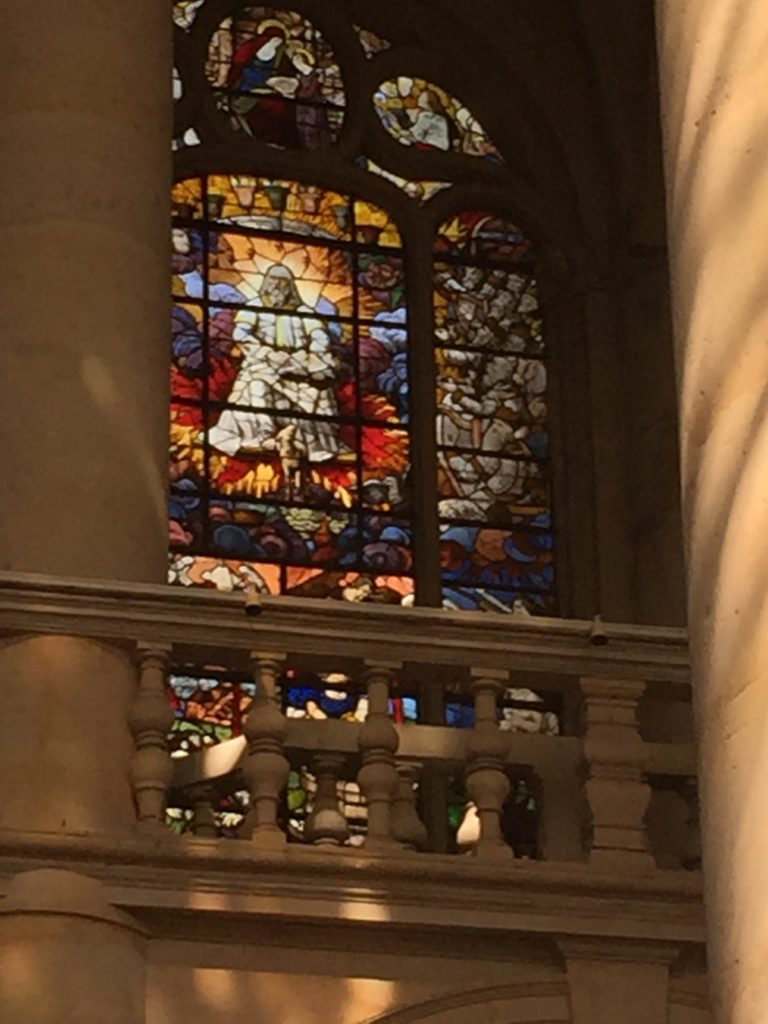

Here are some more pictures of this amazing church:

I have had a passion for church organs since the tender age of 12. I own and run Viscount Organs with a close attention to the detail that musicians appreciate; and a clear understanding of the benefits of digital technology and keeping to the traditional and emotional elements of organ playing.