Since the instrument was first invented, the organ has fascinated players and audiences for its construction and size and its musical tone. I doubt there is any other musical instrument that has evolved so greatly, incorporating new technologies as they become available, and where sheer size has been a driving ambition of many builders.

Years ago, I got into quite a heated after dinner debate with a violinist who suggested an organist could never be a really great musician, constrained as they are by the limitations of the ‘machine’ in their interpretation of a score, denied – as organists most definitely are – the subtleties of volume and tone you can give to a single sustained note on almost all other musical instruments.

Organ development – inventing new sounds

It’s fair to say that the most artistic energy in organ development has been to invent new sounds with which to entertain an audience. Indeed, many instruments have been built that are described as symphonic with the aim to mimic many of the sounds that a conventional orchestra would create. There has been development to make the sound more stable by ironing out irregularities in wind supply and then give the musician some control over speech with ever more sensitive mechanical actions allowing the player to alter the starting speech of the pipes.

Swell boxes were introduced to allow more subtle management of volume. But however good all this is, there is an argument that the organist is more detached from delivering elegance and subtlety than is the case with a wind or stringed instrument. It is hard to argue against these facts.

But is individual musical line the only factor we need to consider when it comes to making really great music? Clearly not. When listening to an orchestra, it is often impossible to hear the detail of each individual part and that does not take away from the ensemble.

One never hears it suggested that a fully occupied, busy orchestra becomes less musical, than an orchestra acting as an accompaniment to a beautiful solo line. And all that takes many musicians, yet an organist is doing all this on his own while also managing a complex machine, all too often not kept in the best of repair.

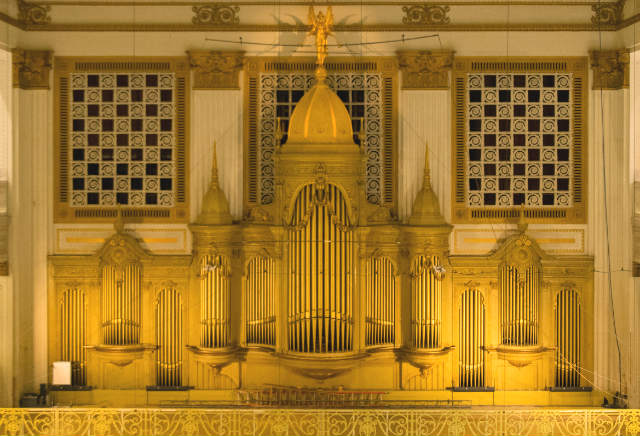

Desire to build organs bigger and louder

There is no escaping the fact that an organ is a large machine. The ambitions of many men have resulted in a desire to build them ever bigger and louder. The Atlantic City Boardwalk instrument being perhaps the best example. 7 keyboards, 3 of them of much greater compass than the usual 5 octaves.

The Wanamaker store (now Macy’s) in Philadelphia took pride in continually adding resources until the instrument was in danger of taking over the store. The drive for scale has been far more visible than the drive for tonal beauty, but organs – especially smaller ones – can deliver the most engaging of musical experiences.

J S Bach created the most wonderful musical creations using independent musical lines that the organ so brilliantly exploits, and Widor, the master of Symphonic organ composition, has created exciting and tender music for the late 19th century masterpiece instruments of Cavaille-Coll.

(Listen to Bach on one of our custom built organs below)

Organ music is music of the highest standard requiring astonishing talent at the console. It’s the reason I’ll consider an organ a beautiful musical instrument rather than a mechanical monstrosity. And you won’t be surprised that I hope you’ll be won over by this argument!

I have had a passion for church organs since the tender age of 12. I own and run Viscount Organs with a close attention to the detail that musicians appreciate; and a clear understanding of the benefits of digital technology and keeping to the traditional and emotional elements of organ playing.