We recently returned to Peterhouse Cambridge to move our Envoy 35-F instrument from the college chapel to its new home in the old Brewhouse where it becomes a permanent addition to practice resources for the College. For the short trip the organ had to be taken across busy Trumpington Street as the new home is just behind the Masters Lodge also on the opposite side of the street to the main College site. We were given special permission to park outside the Lodge for this work.

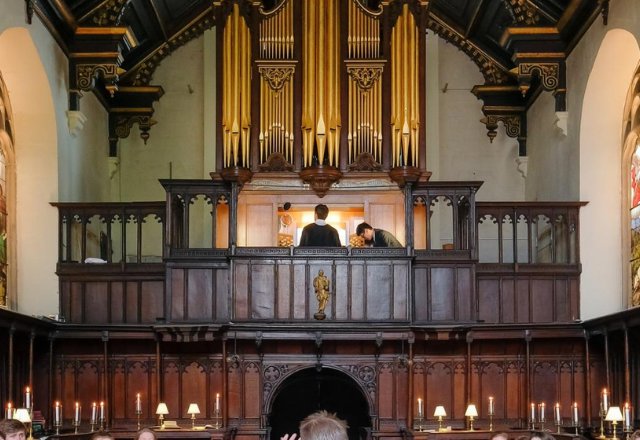

Envoy 35-F in place as historic pipe organ is restored

Our instrument has been in the chapel for over 2 years while the historic pipe organ has been away for restoration by two leading firms of organ builders. Flentrop in Holland and Klais in Bonn. They are now due to return and start the work of reinstating the instrument in what is a really fascinating project combining restoration of one of Britain’s most important historic instruments dating from 1765 by renowned builder John Snetzler, with the addition of a small pedal department and pipes to extend the compass of the original to create a versatile instrument more fitting to the musical and liturgical needs of the 21st century. These additional pipes are to have their own winding.

The ‘Snetzler’ name in organ building is held in very high regard. It’s no exaggeration to say his instruments are considered extraordinary masterpieces of craftsmanship in design and execution as well as for their musical integrity. While the Peterhouse instrument has, like almost all of the other UK’s old organs, been changed over the centuries, Peterhouse is rare in that the Snetzler content remains almost complete and unaltered.

Organ changes through the ages

Early records of the instrument are elusive as Nicholas Thistlethwaites’s researches into the history confirm. The earliest documented information is from about 1842 and confirms an instrument of two manuals. A Great Organ with 9 stops played from the upper manual, a Choir Organ with 8 stops on the lower manual 4 of which are enclosed in a swell box. All of course in 1765 being mechanical action. By 1804 an 8 ft pedal pipe was added by 1830 is seems a choir to great coupler was also added. In 1852 Hill added a 16ft pitch pedal rank. So, the organ escaped any changes to the Snetzler pipe work with just gentle improvements taking place.

Far larger changes were made by Hill in 1893-94 but still the Snetzler core pipework was retained save for his great mixture. All his soundboards however were replaced, and much larger winding was needed.

The instrument was next significantly enhanced in 1964 by Noel Mander but still with very little change to the voicing. A great mixture was reinstated though not to any known Snetzler composition. The action was electrified to allow the Choir and Pedal departments to be enlarged. This must surely have been the most dramatic change to the style of the historic core. Mechanical action gives the musician control of the starting speech of a pipe. Electric action loses this. It would be a bit like adding an automatic gearbox to a Model T Ford. All the character of driving the car would be lost. And so, the nature of this organ changed for ever at this time. Or did it?

The Peterhouse Snetzler is the largest surviving example of his work and so a great plan has been devised to see its resurrection in which I suggest is a very inventive way that allows organ students to experience the instrument Snetzler built in its original configuration while retaining the additions that are crucial to allow the instrument to perform our modern liturgy.

Latest restoration of the Peterhouse Organ

The newly restored instrument will return to mechanical ‘balanced’ action as originally built in 1765.

The original foot treadle winding will also be reinstated alongside a blower driven supply. And finally, there will be two consoles. One as originally installed on the east side of the console where just the Snetzler stops will be found, and one on the north side where all stops can be played.

I wonder how many volunteers there will be to provide the wind power to play the instrument exactly as it would have been in 1765?

Winding by the way is another very important factor in the how an instrument sounds. If I may drop into my motor car analogy again a Model T Ford with a modern engine will also feel nothing like it did when rolling off the production line. This arrangement opens up a whole new option for organ duet playing but I very much doubt that entered into at all the design settled upon for this rebuild.

For any musician with an interest in the history of the organ this rebuilt instrument will be a fascinating example of how the passage of time has changed musical tastes and technology has enabled these changes to become manifest.

Hearty congratulations to all involved in this project which I very much hope will set a new standard by which future organ rebuilds can successfully merge the best of many eras without loss of quality and flexibility to support the musical needs of today.

I am indebted to the work of Nicholas Thistlethwaite for the information I provide on the history of the Peterhouse Organ.

I have had a passion for church organs since the tender age of 12. I own and run Viscount Organs with a close attention to the detail that musicians appreciate; and a clear understanding of the benefits of digital technology and keeping to the traditional and emotional elements of organ playing.

This is really interesting. I love the analogy of the Model T Ford.

I shall follow this with interest