This post is part of a series where I share some of my world travels on which my love for organs has taken me. I help friends, associates and fellow organ lovers with projects that mean I get to see new and old organs in gorgeous settings and really experiment with this instrument.

For six months I had been looking forward to my visit to Toulouse and assisting at one of Cavaillé-Coll’s greatest instruments. The experience lived up to and beyond the expectations already set by the instrument’s reputation.

It is interesting: we live in an age where we crave technology that moves so fast, obsolescence sets in within little more than 12 months. Yet at Saint Sernin we are able to hold in high regard an engineering masterpiece some 130 years old that is as fit for purpose today as it was when new. I can think of no other technology of which the same can be said. We might enjoy driving a vintage car or even using a wind up gramophone, but surely not every day?

Yet a magnificent historic organ seems timeless. It retains a dignity that would be hard to emulate today and in the case of the instrument at Saint Sernin, completely unaltered since it was built, it remains a joy to hear and play.

Not without its eccentricities…

It is true that a capture action would simplify matters for page turner and performer. The ventils require an additional level of dexterity to manage and in some cases considerable physical force. However even those, after a time, become part of the charm of playing the instrument.

These foibles are part of its character, defining timings for registration changes and often, with manuals coupled, dictating a tempo that however much you may wish to exceed is limited by what the instrument allows.

In most other daily tasks we have eagerly adopted improvement and actually hungrily anticipate it. However, with Cavaillé-Coll instruments, the only concession to progress needs to be electric lighting and of course, electric blowers.

Many of these instruments even retain the foot treadles for the bellows but I rather doubt they are ever used now.

In the case of Saint Sernin, even the original oil lamps (pictured right) that once lit the console have been retained. Playing by these flickering lights must have added to the challenge and sometimes, in a very cold church, they may have also been welcome as a tiny source of heat.

My tour of Cavaillé-Coll instruments

I have now had the privilege of assisting at Saint Sulpice, Saint Ouen Rouen, La Madeleine, Saint François des Salles Lyon, and most recently Saint Sernin. Each instrument has a different character.

Saint Sulpice (1862) is by far the largest instrument with the loft console the most remote from the pipework, at least from the Recit organ which must be some 20 metres above the console. So while the instrument has a huge range of colours, some of these are very distant and are heard far more strongly in the building than at the console.

St Ouen (1890) is a magnificent beast, whose Bombarde reeds are the most thrilling of all the instruments. This instrument is also by far the most difficult to play today. The church is no longer used for services so I imagine that the maintenance needed to bring it back into near new condition is difficult to finance – and hard to justify.

La Madeleine (1848) was the third largest instrument built, and included the first ever 2-rank stop named Voix Celeste. A brass plaque beside the door to the loft steps celebrates this invention of Cavaillé–Coll.

It also has a sophisticated (by standards of the day) stepper facility that allows the page turner the plenty of time to set up the next registration and then pull just a single stop to make the complete change: a real godsend for the assistant. As the organ has been altered further by later builders, I wonder if this stepper facility was a much later addition? As it was such an obvious benefit, had it been available in 1848 why would it not have been used on other instruments in the meantime?

The pipe case at La Madeleine is also very different in character from Cavaile-Coll’s other instruments. By contrast, its design is quite severely restrained. The case has a very neo-classical façade that echoes the design of the building which would not be out of place if it were set alongside the Parthenon.

The organ’s sound seems to mirror the case design – it is very refined. The pipe work high on the West End wall has no lower positive case so the musician faces the East, which creates a feel that is very different from that of the other three West End organs where the musician is hemmed into a small space between the positive organ case and the main case. The absence of a 32 ft reed in such a huge building also creates a slightly understated sense of full organ.

St François des Salles (1880) by comparison with the other four is a “boutique instrument.” However the close proximity of the console to all the pipe work adds greatly to the performer’s enjoyment of the instrument, even if it does lack the scale of the others I have experienced. It is the nearest you will get to a Cavaillé–Coll that you might just be able to sneak out of the building while the Sacristan’s back is turned, and whisk away for your private enjoyment!

In my opinion Saint Sernin (1889) manages to combine all the best features of the instruments mentioned above. There is abundant power without quite the brutality of some of the St Ouen reeds. There is not as much stop choice available as at Saint Sulpice, but the console is more intimately placed so the performer has a stronger connection to the colours available. Consequently, control of the articulation is a little easier to manage.

The favourite so far?

It would be a privilege to be able to play any of these instruments on a regular basis and picking just one is a very hard choice, but if forced into a corner I think Saint Sernin wins by a small head. Can it be a coincidence that it was nearly the last organ Cavaillé-Coll personally supervised before he died in October of 1889? I would like to think that here sits the culmination of expertise from a great engineer and artist, who applied what he had learned from all his past commissions in this truly spectacular final instrument that is kept in marvellous working condition to this day.

If my luck continues I look forward to going on the Desert Island Discs radio programme and declaring that the only luxury I would need is a Cavaillé-Coll from anywhere to take to my island – as long as there was power for the blowers. And my book, of course, would be the works of Widor. The only remaining problem would be being good enough to play the instrument – but then I guess there would be plenty of time for practice.

Meanwhile, in Saint Sernin…

Happily on this visit my only role was turning and registration. This session would finish off a complete works set of Widor for my employer. The main work was the Romaine Symphony, actually written for the Saint Sernin instrument, with two jolly pieces to make weight: the March American in a transcription by Dupré and the March Nuptial. For good measure we also put down another version of the famous Toccata from the 5th Symphony.

The experience of first walking into a great church or Basilica is always a special one. Entering for first time, if at all possible I do so from the west end as this gives an immediate sense of scale which in most of these great locations is usually stunning and Saint Sernin is no exception. (See left for a picture of the Nave). My next decision, indeed a little game I play with myself, is to walk in avoiding the temptation to look back too soon to the west end. Too soon and the organ may not all be in immediate view; too late and it may seem too far away. How sad! But there is only one opportunity to make a first impression and I want that to be as glorious as it can be.

Saint Sernin, being Romanesque in design, is relatively narrow and the organ is set back tightly between the aisle walls, but the view is of an instrument of great beauty and perfect proportion. (view of organ in picture below).

Our first task was to meet the Custodian and receive detailed instruction on the building’s locking protocol which as you might expect was complicated. I am afraid to say on our second night after a long recording session we failed to execute this perfectly. Next day we rightly got a sound telling off and the locking up thereafter was carried out with no mistakes.

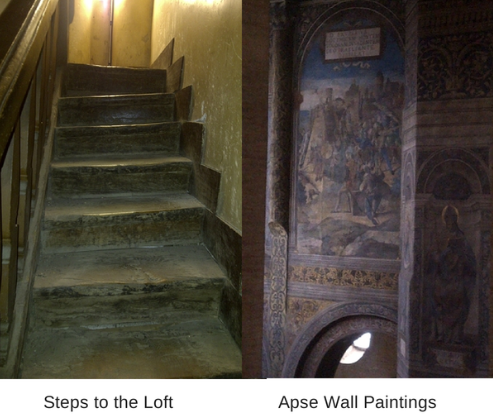

We were also given a private tour of the triforium level from where we could look directly down onto the 18th century altarpiece, (see picture below of altar piece from the triforium) a view not seen by many visitors. There followed a tour of the crypt which is open to the public and contains many wonderful monuments, with the apse walls behind the altar covered in fine paintings.

Unusually for such a large building there is no heating and winter services are regularly carried out near 4 degrees C. The priest can wear heavy robes but the organist has to play in gloves. Summer temperatures can reach the high 30s so the challenge the organ tuner faces must be considerable. Despite enduring over 100 years of these huge temperature changes, the instrument plays very much as I imagine it did when it was first built. Anyway it is hard to believe it could be much better.

We at last climbed the loft steps around 6 pm on the first day, waiting for near closing time so as not to disturb visitors. The steps show great age and indeed the second flight leans at about 15 degrees to the left throwing you onto the hand rail as you ascend.

Once you are at the top, a tiny landing allows you to unlock and then you must duck to avoid collision of head with very hard stone. This was a challenge I all too often failed to remember in the numerous runs down to the improvised studio in a side chapel as my performer went to review the takes on headphones.

The recording itself

The engineers arrived from the UK and a bundle of equipment was unloaded and set up, including a telescopic stand that must have risen 30 meters off the ground placing the microphones almost directly in front of the Recit pipes. Various tests then followed, closer, lower, higher and more distant until the best result was found.

Our first night of recording started at 8 p.m. On entering the Basilica we were overwhelmed by a wonderful smell of incense. This lingered for a full two hours, reinforcing the very special circumstances in which we were working. All went well and the entire symphony was completed that night, helped considerably by some light rain that cleared the square of noisy students – Saint Sernin being in the heart of the university sector of the city.

We had our usual comedy incidents. In my case a few stops too soon or too late and in my performer’s case some missing ventils, so the stops were on but deprived of air. Sitting as one must on one side of the musician, the registrant can only help with no more that half the ventil or coupler toe pedals and from time to time I do. Ventils to the far side of the musician are just too far away. Not even a master’s graduate from the John Cleese’s “Ministry of Funny Walks” could possibly reach those without a clash of legs under the console … with inevitable dire consequences.

After 30 minutes or so we began to hear a regular clanking. My first thought was that Christmas was early and Marley’s ghost had come to pay a visit. Believing we were alone in the Basilica we presumed someone was trying to, or even had, broken in. What to do? Who to call? Investigation revealed it was the Sacristan making his nightly round emptying the money boxes and refilling the candle racks for the next day. Nothing, but nothing was going to interrupt this ritual and so proceedings stopped for 20 minutes until the sound died down.

As ever the notes were flawless and I was impressed by how easy it seemed where a section requiring thumbing down from Recit to Positiv was played. I struggle with two manuals, (well actually if you were to speak to some of my friends I struggle with one manual,) but all three manuals at the same time? That needs an altogether higher skill level than I will ever have.

Just before midnight we concluded and happily found a café still open in the city square. Much needed croques monsieurs and wine were consumed, with us finally walking back to the hotel through an almost silent city near 2 a.m.

Recording, night two

We started night two with a modest challenge: two very light hearted pieces and the toccata from Widor 5 that I know my employer could play easily from memory, so the page turning was not overly important. We needed a second registrant for one piece and this was ably carried out by our recording engineer’s son, still at school but clearly a very promising musician already studying harpsichord. I tried to tell him of the error of his ways in instrument choice but I rather think that exposure to the Cavaillé-Coll may well have done that job far better for me. But he will of course have to be content with more modest instruments when back in the UK for his daily fayre. I will also have to watch my back; he was far too proficient for a first time stop puller.

Starting at 6 p.m. we had the enjoyable prospect of an early finish and a relaxed meal to look forward to. If you have read my blog post about Lyon you will know I was not impressed with the food there. Toulouse however is a very different place with an abundance of restaurants of all prices offering a great variety of French cuisine. I could happily eat there for weeks. We found by chance a great restaurant which only offered steak and frites and the wine selection was equally uncomplicated: red or white. We dined early and by the time we left, this large restaurant was full with a queue of about 20 in the street waiting for a table. Never saw that in Lyon!

Anyway I digress. Night two went equally well and we were even prepared for the Sacristan’s noisy ritual. What else? Widor’s toccata. This was not in the slightest bit interrupted by the coins or the candles. Probably a bomb could have gone off as well and we would not have noticed. Indeed some years ago a nearby factory exploded and to this day one of the Basilica side doors no longer closes properly without considerable effort. One needs to claquer this particular porte very hard to get the job done. I wonder if Michael Caine was in town at the time?

And finally…

The organ of Saint Sernin is a triumph of design, construction, and marriage within a building of immense scale. When the organ was first installed the church had plastered walls. These are now stripped back to bare brick; a job done in the early 1900’s which must have slightly reduced the acoustic bounce from the walls. Today the sound is immense. I can only imagine how it must have been before the plaster was removed. Whatever the change, there remains today a sound that I very much doubt any modern technology, be it new pipes or any digital invention will match or surpass.

Congratulations to all those who created it, care for it and have the skills necessary to play it. Saint Sernin is one of life’s very special places. It was a privilege to have been allowed so privately to enjoy the magic of the building and the organ.

If you are interested in my travels and organ experiences, make sure you follow the series. Similarly if you have had a great (or even a small) adventure with an historic organ and want to share it with me and my blog readers, then please feel free to comment below and let us know all about it.

Skyline image at the top of this post – courtesy of: sergein / 123RF Stock PhotoI have had a passion for church organs since the tender age of 12. I own and run Viscount Organs with a close attention to the detail that musicians appreciate; and a clear understanding of the benefits of digital technology and keeping to the traditional and emotional elements of organ playing.

Dear Sirs,

I often wondered if the registrants at St.Suplice are actually permanent employees or do they get some sort of payment as it would appear to be nearly impossible to play this vast instrument fluently.

Hi Ross,

Good question and I do not know. Many registrants are happy just to be in the loft and experience the instrument close up. There is a ‘preset’ facility on the St Sulpice organ that allows registrants to move the stops to the next setting without the voices changing. Then pulling just a single stop moves the whole instrument onto the next set up. Use of the ventil pedals also allows the musician some degree of freedom and actually once you have got the hang of these ‘playing aids’ its not quite as fearsome as it looks! Regards David